Share |

Music: Mythic Elements in Works for the Musical Stage: The Unknown Prince and the Trickster

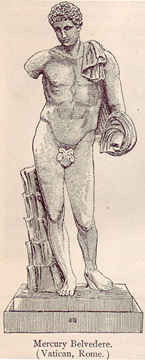

“A Roman Statue of Mercury (Hermes)”, the First Trickster in Western Classical Myths. “A Roman Statue of Mercury (Hermes)”, the First Trickster in Western Classical Myths. |

By Frank Behrens

ART TIMES November/ December 2011

In the first part of this series, we considered the Unknown Prince theme in “The Mikado,” “Turandot,” “The Magic Flute,” and “Lohengrin.” When it comes to light opera and what we call the Broadway Musical, that archetype persists.

The most obvious example is that of “The Student Prince.” But there is no magic. Cathy easily falls in love with a student, who in reality is Prince Karl Franz. And his departure at the end to take up his duties as King leaves only the magic of a brief but beautiful romance that could not last. Nothing much mythical here. So on to another archetype.

There is a character throughout world mythology known as the Trickster. Children in this country know him as Bugs Bunny; those of many decades ago knew him as Br’er Rabbit. African tales are filled with these troublemakers. In the Viking tales, he was Loki, the personification of fire, a very unpredictable element that can do great good or great evil.

In some tales, the Trickster wins out. In others, he is himself tricked. The point seems to be that even those who act against society can leave behind some benefits to the society they harmed. Such is Harold Hill, the Music Man himself.

Here the Trickster is a simple con man posing as a Prince, or at least as a band master. Harold Hill’s racket is to sell uniforms and band instruments to the children of a given town, with the promise that he will turn them all into a wonderful town band. Convincing the citizens of River City, Iowa, that the evils of the Pool Hall must be exorcised by the Good Influence of music, he get lots of money but makes a fatal mistake. He falls in love with Marion the Librarian.

Little by little, as is expected in this sort of Americana tale, she brings out the good in him. When the uniforms and instruments arrive, he tries to use the Think Method on the children. That is, if they think about what they wish to play, they will indeed play it! When arrested and told to make good on his promise—I can only assume that all of my readers know the end, so I am not afraid of spoiling things—the children come through! Terribly, but the parents are happy enough; and loud cries of “That’s my son/daughter” fill the room. And no one is more surprised than Harold Hill himself.

Mythical? In a psychological way, because there was a real Prince always at the core of this trickster. So all can end happily. River City is a better place for his having been there, and wedding bells will ring for Harold and Marion.

The plot of “The Music Man” can be compared to the tale of Jason, if one uses considerable latitude. Instead of sailing off to find the Golden Fleece, Harold Hill takes up a challenge in the train sequence that opens the show. His Golden Fleece will be to fleece the population of River City—known for its xenophobia, which is the equivalent (if you push a little) of the dragon that guards the fleece.

Marion isn’t exactly the ready-to-kill Medea; but in fact she acts as the antagonist when she proves Hill to be a liar. However, she is finally conquered by his charm (a quality certainly lacking in the original Jason) and encourages him to win the “fleece” by convincing the parents that they were not fleeced at all.

Sky Masterson in “Guys & Dolls” is a sort of trickster when he makes a bet that he could get the lovely but sedate Sarah the Mission Girl to come with him to Havana. He wins it by promising her that he will fill the failing Mission with sinners and so save it from closing. The trickster is tricked and finds himself in love with Sarah, and only an appeal to the gods—or, in this case, Lady Luck (Fortuna)—makes it all possible. The mission is saved and the guy gets his doll.

The Broadway musical has produced one great female trickster, Ella Petersen in “Bells Are Ringing.” Taking advantage of her position of message-taker at Susanswerphone, she knows the needs of her clients and takes several disguises (vocally over the phone, physically in person) to help them fulfill their fondest wishes. So she gets a composer-lyricist dentist to have his show produced, the handsome lead’s writing talents to rebloom—as does her love for him and belatedly his for her—and so on. In short, she is the Trickster of myth that brings great benefits to the community.

So we have considered some examples of the Unknown Prince and the Trickster. What next? A secret until next issue.

fbehrens@ne.rr.com