Dance: Flamenco The Antonio Gades Way

By Dawn Lille

October 1, 2016

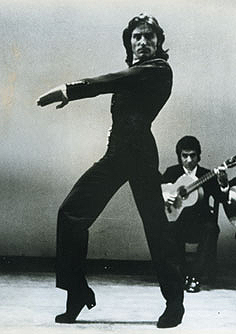

Antonio Gades |

In a Spain filled with summer performances, the Porto Ferrado Festival in Sant Feliu de Guixols is among the oldest. One of the highlights this year was Fuego, a ballet inspired by the music of Manuel de Falla’s El Amour Brujo and presented by the Company Antonio Gades.

Antonio Gades (1936 – 2004) was Spain’s greatest dancer and choreographer. The three films he made with the director Carlos Saura, Blood Wedding, Carmen and El Amour Brujo, brought his concept of flamenco to millions throughout the world, allowing them to witness him as a dancer as well.

The third, made in 1986, was their last together and it went even further in expanding Saura’s love of flamenco and his influence on Gades, who was able to realize many of his own ideas through the filmmaker.

Gades was born into a poor family headed by a father with strong Communist leanings. He left school at 11 to work and was seen performing in a bar by Pilar Lopez, head of Spain’s largest dance company. She took him into her school, where he was trained and then accepted into her troupe. He left Spain to study ballet in Rome and became a leading dancer in the ballet company at La Scala in Milan.

He was invited by Alicia Alonso to dance with the National Ballet of Cuba in 1977 and spent time in that country. Although he broke with the Communist party in 1981 because of Stalin, the two constant passions in his life were politics and dance.

In 1978 Gades was made head of the new Spanish National Ballet, but left in 1980, taking most of the dancers with him. They formed Ballet Antonio Gades, which performed in NYC in 1984. He had previously formed other companies, one of which was seen at the Spanish Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in 1964. Given his deep political beliefs, it is not surprising that his last company, the one that still exists, is organized as a cooperative.

As a dancer, Gades was slim and remarkable not so much for his technique, but for the intensity of his elegant movement, which emanated in a direct line from his eyebrows to his feet. Many saw him as erotic as well, and he was quoted as saying, “You have to caress the ground.” His heel work in particular, spoke to the space beneath it. (Take a look at him dancing the farruca in the film of Carmen, available on UTube.)

His choreography was a fusion of ballet and flamenco and he elevated Spanish dance to a position of equality with classical ballet. He advocated a return to tradition for anyone wishing to evolve and create change. His own work was more abstract than traditional flamenco.

De Falla composed El Amor Brujo [Love The Sorcerer] as a ballet for symphonic orchestra in 1915 and transformed it several times afterward, adding traditional flamenco songs and making it into a sextet, among other versions. The easy to listen to score remained an attraction for Gades throughout his life.

Company Antonio Gades (Photo: Javier del Real) |

The plot concerns a young gypsy girl, Carmela, who is tormented by the ghost of her dead husband, called Espectro in this version. As a child she is promised to him by her parents and they are married, in spite of her love for the young Carmelo. Her husband is killed defending the honor of his mistress, but his ghost forces Candela to dance with him every night. The village women tell her he was unfaithful and the town organizes against the ghost and the dark evil he represents. In this version the mistress becomes Hechicera, the witch whose intervention helps to eliminate the ghost via the ritual fire dance. The ballet ends with the wedding of Candela and Carmelo.

In 1989 Gades decided to make a new ballet using the story and de Falla’s music, adding different flamenco songs and other popular music. More dream-like than the film, it was a culmination of much of his work until then. He changed the title to Fuego [Fire] and the work premiered in January, 1989, in Paris. A tour of Europe, Japan and Brazil followed. Due to his personal problems at the time, it was not seen in Spain until July, 2014, the tenth anniversary of his death. Today his ideas are carried out by the company and a school, both under the Gades Foundation near Madrid.

There are 22 members in the company, including two singers and two guitarists. The women are of various ages, although one, dressed in red and a bit fuller in figure, with a classic Spanish face and hair parted and pulled back, somehow seemed to delve deeper in eliciting emotion. This was Hechicera, danced by Stella Arauzo, the company’s artistic director, the reconstructor of the ballet and the original Candela.

As is the case in all flamenco groups, everyone sang and created intricate rhythms with their palmettos (hand claps) and the musicians and singers filled in as dancers. De Falla’s score was heard on an orchestral tape, alternating with the live music.

The role of the people, the pueblo, is tantamount in all of Gades’ work and they play a large role in Fuego. Their reactions look spontaneous, but there is no improvisation in his dances. Every movement and reaction was carefully set by this perfectionist to give the impression of spontaneity. The final result, as seen in Sant Feliu, is that of dance, drama and music meshing in a constant unfolding, often cinematic in nature. There were balletic elements, observed in the beats of the legs and curves of the arms.

Costumes were not the traditional flamenco ones, but the women’s long dresses were full enough to flounce when they so desired. There was fast, concentrated, rhythmic footwork by individuals and the crowd, but this dance was created for a community. Sometimes they moved like a wave coming onto shore, supporting Carmelo or protecting Candela. Other times they united in telling her she was free to continue her life. The young couple appeared almost in silhouette during the fire dance and were joyful as they were each raised up after their wedding.

Gades called Fuego a combination of passion, mystery and death, elements he found in both the music and the Andalucian folk myths on which it was based.

The production reached out to those sitting under the Spanish sky on a warm summer evening, projecting the light that overcame the darkness in the tale.

dawnlille@aol.com