Dance: Speaking Without Words: Using Dance As A Language In The Architecture of Medical and Social Information, Education, Awareness and Advocacy Contributing to Public Health

Part 1: The intersection of dance and medicine: using dance as a language in the architecture of medical education

By Andrew Carroll,

ART TIMES July 2014 online

|

Within the artistic community, one can say that dance in contemporary times exists as a statement of the choreographer or dancer, each committed to communicating something to an audience. Regardless of whether the work that is created is literal or abstract, the desire and need for self-expression propels the artist to create. Therefore, many times when viewing a work of art (whether it is a dance, painting, sculpture, poem, etc.), the audience is being challenged by the creator of the work to think about what the work of art represents or evokes. Choreographer and writer Agnes de Mille stated that work of art are “symbols through which people communicate what lies beyond ordinary speech…art is communication on the deepest and most lasting level.(Ambrosio) 1 In addition to communication, choreographers can and often wish to impart meaning, atmosphere, mood to further explore and expand the parameters of what is presented as a final product. Whether through live concert means or in more contemporized mediums available through the digital age, this final product often reflects the personal ideas and or statement that the respective choreographer wishes to impart. Long hours of experimentation with movement are often undertaken to deliver these elements. One can say the artist is imploring an audience to listen, to think, and to reflect on what they have chosen to verbalize through the articulation of movement. The power of dance to communicate facilitates this individual creative need. The suggestion to incorporate dance’s power to communicate via this platform as a means to educate and to facilitate awareness to the fields of medicine and sociology is not often envisioned, yet this intersection emerged through a creative project involving The Florida Department of Health, and The School of Theatre and Dance at The University of South Florida. The resulting projects proved to be significant in that a new language in the architecture of educational strategies desired by the medical and social fields to disseminate information via new media platforms has been created which utilizes the arts via dance as the means of transmitting ideas. In addition, they have profited the dance genre by the sheer volume of audience participants who view and experience the artistic contributions of the choreographer, dancers and of dance at large.

The Initiation of Project and Identification of Researcher

In 2010, The School of Theatre and Dance at The University of South Florida was contacted by The Florida Department of Health regarding a creation of a new tool in their instructional landscape for new cleaning staffs. Specifically, the FDOH sought the creation of a dance video which could be presented as an introduction to vocational education protocols using dance as a universal language that through uniqueness, could both engage viewing and transcend language barriers. In addition, this new product could access new media, ie: shared via technology whether through links, social media pages or Youtube.

As a Professor of Dance in The College of The Arts at The University of South Florida, I was the faculty member who was approached to embark on this creative venture. From a choreographic standpoint, this project presented the application of my genre to an as yet uncharted territory. Artistically, any challenges arising from this unexplored landscape ultimately could be seen as conduits to discover new movement possibilities, adding to my own personal movement vocabulary. This prospective cache of invention was seen as an avenue for new growth and expansion creatively. Additionally, I was intrigued with the possibility to generate a fresh idiom in which to articulate ideas and concepts that are beneficial to the awareness of social and/or medical issues. Beyond the creation of a new informational system in the landscape of social and medical education, the project presented the possibility of an instrument that could introduce dance, and its power to communicate to new audiences, many who might experience this art form in a brand new fashion, or even for the first time. From an interdisciplinary perspective, this project facilitated the union of two genres not accustomed to join forces in the respect of educational process. Yet, the idea of using dance in this fashion could fill an existing hole that separates the arts from other disciplines. In this age of advocating for more global collaborations, this project could sew together two otherwise dissident worlds together. Therefore, due to the compelling nature of these propositions, I accepted the project and began the process of building this assignment.

Dance as Communication

|

Art at large has existed through millennia as a means of communication. Dance, in a broad aesthetic definition, has existed to describe a wide range of messages through movement: emotions, atmospheres, storylines, and pure athleticism among others. Dance belongs to an arsenal of movement training techniques that lay at the foundation of every cultural community as “tacit knowledge.” Sensory, emotional, and perceptual experiences are stored in movement, gestures, and rhythm. This knowledge relies on verbal and gestural traditions of cultural transmission and is made material in artifacts or nonverbal forms of communication.( Baxmann)2” This method of communication can exchange ideas and has often served to describe and illustrate when words fail and only feeling exists. Choreographers recognize the value of this aspect, and sometimes utilize this means to convey precise meaning through their craft. Dance is usually seen as a medium through which information, messages and ideas are communicated by the dancer’s body to onlookers. The dancer engages in movement patterns which are often symbolic and sometimes reflect some true life situations. (Abraye, Kansese)3 In reality, this concept or idea stretches from time immortal. Gestural efforts and rudimentary pantomime have served to communicate ideas and concepts either due to lack of language, or the differences that reside within diverse geographical or ethnic vernacular. This “acting out” of prose can facilitate understanding at a deep core of universal human physical recognition. At base level, movement can be understood more often instinctually by a broader spectrum of viewers, in spite of cultural, geographical or language barriers. Indeed, at times physical movement suggests the essence of that which is desired to be communicated fundamentally with more validity and honesty than mere words. For example, the physical gesture of a hand gently touching a loved one’s cheek imparts love at times deeper than the words “I love you,” and the simple physical upturning of the palms towards someone to whom you have grieved sometimes conveys remorse stronger than stating the words of “I’m sorry.” “ Gradually, appreciation is increasing for the roles of movement, emotion, and bodily sensory memory in the production and staging of knowledge.( Baxmann)4 ” Perhaps this appreciation and the instinctual connection and recognition of movement can extend exactly towards a “staging of knowledge” when they are developed towards an explicit educational motif.

This alternative means of articulation yields another beneficial advantage: ideas that are verbalized through movement can be understood across diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds. This notion proves valuable to participants in the world of dance. Dancers can and do walk into studios worldwide to partake in classes offered with little regard to language beyond “where is the bathroom,” or “where do I catch the bus.” The communication necessary is that of the physical nature, and understood whether one hails from Russia, The United States and all points in-between. The classes themselves prove to be no more of a problem beyond the usual “dancer” constraints and challenges of skill and stamina; language within the structure of technique class is not often of primary concern. This can be regarded as a unique facet that the world of dance attains. This can be of benefit to those who are not practitioners, especially when it can be applied towards distinct educational measures that utilize dance to potentially reach diverse populations.

In regards to communication, one must also look to the means of communication, and specifically modes of transferring information in the digital age we live in. The use of dance in the absence of language may have existed for centuries, but today our means of communication also encompass the vast landscape of technology, where texting, tweeting and other means of technology substitute spoken words. How can dance stay relevant and continue to serve as a means of communication in this digital age?

Similar thoughts contributed to the appeal for The Florida Department of Health to envision the idea to use dance and movement for an educational video to inform new cleaning staffs about procedures necessary for thorough and effective cleaning of hospital rooms, specifically in reference to Clostridium difficile.

According to the Mayo Clinic, Clostridium difficile, often called C. difficile or C. diff “is a bacterium that can cause symptoms ranging from diarrhea to life-threatening inflammation of the colon. Illness from C. difficile most commonly affects older adults in hospitals or in long term care facilities and typically occurs after use of antibiotic medications. In recent years, C. difficlie infections have become more frequent, more severe and more difficult to treat. Each year, tens of thousands of people in the United States get sick from C. difficile, including some otherwise healthy people who aren’t hospitalized or taking antibiotics. Mild illness caused by C. difficile may get better if you stop taking antibiotics. Severe symptoms require treatment with a different antibiotic. 5. In addition, Clostridium difficile (C diff) is a Gram-positive, spore-forming, toxin-producing, anaerobic rod bacteria that results in millions of human infections worldwide annually. The annual incidence of C diff associated diarrhea (CDAD; some refer to it as C diff associated disease) in the USA is more than 250,000 cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (McFee)6

Realizing the pantomimic imagery described through dance can transcend language barriers, and as such, can be an accessible means to facilitate the exchange of information, The Florida Department of Health desired such a means of communicating C-Diff elimination methods. This means was coveted for the diversity of staff who populate the employment pool; the expression and communiqué of dance can be preferred over spoken or written means of education especially in regards to employees who may not have sufficient skills in mastering meanings or instructions based in the English language. The “language” of dance can rise above this challenge.

In addition, dance/music videos maintain a distinction of popularity. For years, television channels have been devoted to their presentation; commercials and concert tours among other venues have featured this medium for entertainment purposes. “Is it the music?” “Is it the physical or instinctual moves which accompany the music?” Rather, it might be the marriage of these two beloved art forms, dance and music, a union which satisfies and complements each entity in ways that is favored by diverse groups of people. As a result of their popularity, often a dance/music video is viewed on multiple occasions, a fact which does not escape an organization who may benefit from repeat viewings, or one which hoped that repeat viewings might incur a deeper understanding if information could be embedded in it.

This ideas have recently been behind the idea of a 2011 BPS Public Engagement Grant project entitled ‘Communicating psychology to the public through dance,’ involving Lucy Irving from Middlesex University and Professor Andy Field from The University of Sussex. Similar to the Florida Department’s desire to use dance to communicate ideas, Irving and Field saw dance as a conduit to illustrate statistical concepts necessary for education within the field of psychology. Parallel to the proposed medical video, the BPS project encompassed working with a choreographer to illustrate concepts for psychological education. The resulting four short dance works depicting statistical information appear on the BPS You Tube Channel. Irving is quoted as stating “We hope that representing complicated psychological constructs and statistical procedures in fun and memorable ways will enable more psychology students to understand and engage with them.” Irving further discusses “The project is at an exciting stage as we see how the choreographer has interpreted these concepts and worked with the dancers to illustrate and bring them to life. Our hope is that as well as being fun and unusual the dancing will demystify and create more interest in statistical literacy.” (Irving)7

In light of these facts, in 2010, The Florida Department of Health sought to create this type of innovative instrument that addressed C-Diff elimination protocols. Specifically, they desired to use a video that used dance to train multi-lingual Environmental Services Staff on cleaning high-touch surfaces in patient rooms. This included the procedures of both daily and discharge cleaning. Dance was considered as the medium for information exchange due to the several reason discussed: accessible communication, and the popularity of the medium and its subsequent possible outcomes among them.

Subsequently, The University of South Florida was approached by The Florida Department of Health to flesh out and invent a dance video based on the needs of proper C-Diff protocols.

Anne Carol Burke, The Florida Department of Health, Bureau of Epidemiology states:

“The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) Healthcare-associated Infection Prevention Program worked with The University of South Florida, School of Dance to develop a training video for healthcare environmental services staff on cleaning high touch surfaces in patient rooms and the proper donning and doffing of gowns and gloves. The FDOH wanted to take an innovative approach to enhancing existing healthcare environmental cleaning programs and use dance as a method to train and inspire environmental services staff in a way that was interesting, easy to understand by a multi-lingual workforce, and motivating.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines healthcare-associated infections as those infections that patients acquire during the course of receiving treatment for other conditions within a healthcare setting. Healthcare-associated infections are one of the top ten leading causes of death in the United States. The Florida Department of Health, Bureau of Epidemiology, received grant funds through the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to support Healthcare-associated Infection (HAI) Prevention Program activities. As part of this program, the DFOH, in concert with a multidisciplinary advisory board, selected two of the Health and Human Services (HHS) healthcare-associated infection prevention targets, catheter-associated urinary tract infections and Clostridium difficile infections, to address in their 2011 prevention collaboratives.

To participate in a collaborative healthcare facilities were required to implement evidence based prevention strategies to reduce infections. These strategies are most effective when implemented together or in “bundles.” The proper cleaning of patient rooms is an example of an evidence based prevention strategy, and critical to preventing the spread of Clostridium difficile. It is essential that healthcare environmental services training programs re-enforce cleaning of high touch surfaces in patient’s rooms, and the proper use of personal protective equipment such as gowns and gloves when cleaning isolation rooms. Another example of an evidence based prevention strategy is the proper cleaning of hands or hand hygiene. There are several videos on the internet that encourage and support hand hygiene practices in an entertaining yet educational fashion suing dance, miming and other theatrical activities to demonstrate proper hand hygiene techniques and re-enforce the importance of hand hygiene. The FDOH sought a partner who could employ these same concepts for developing a video on cleaning patient rooms and proper donning and doffing of gowns and gloves. (Burke) 8

From an artistic approach, this creative project presented itself as an interdisciplinary research venture, pairing two distinct fields that in most circumstances do not join together in regards to research. Initially commissioned for The Florida Department of Health, the process proved successful enough beyond the initial commissioned video to reap two subsequent commissions and spun off to produce similar videos that branched into the social arena via videos on bullying and domestic/dating violence which will be discussed in Part 2.

Methodology

|

Dance and Clostridium difficile, a bacterium responsible for infections within the hospital setting seem an unlikely pair in any collaborative fashion. Dance, well, is dance; an art form that uses the human body as a medium to express communication or to display choreographic ideas through movement. Clostridium difficile, or C-Diff, is a medical issue, one targeted towards those who may come in contact with it and those who are responsible for its elimination. When one looks at the commonalities between the two, few come to mind. Yet, The Florida Department of Health saw an innovative possibility of how one could help the other via the medium of a dance video that might illustrate proper cleaning procedures necessary for elimination of C-Diff. Specifically, The Department of Health hoped for a new instructional tool to augment education and engage staff intended to communicate initiatives and protocols necessary for effective C-Diff removal for daily and discharge cleaning.

Choreographically, each of these research projects involved envisioning concepts that could illustrate initiatives necessary to convey educational messages. To understand these initiatives, I, the research choreographer, underwent training in an actual hospital room which had offered its services to teach me the actual cleaning procedures and protocols. This research process was necessary for each subsequent video to begin to build a framework for the video projects. The research process included the following lists of desired outcomes portrayed through movement for each of the following videos that have been produced:

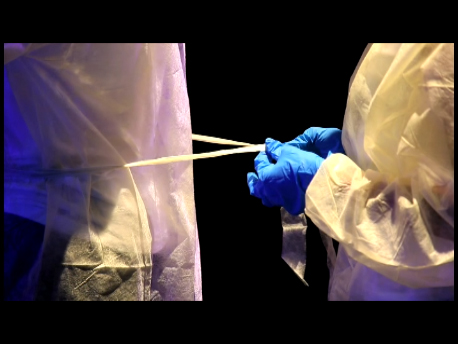

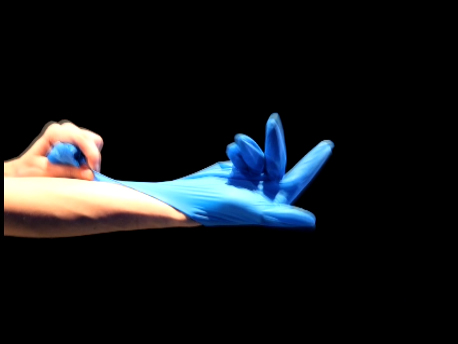

Video one “Cleaning Patient High Touch Surfaces”: the identification and cleaning of high touch surfaces within a hospital contact isolation patient room setting, donning and doffing of PPOs (gowns, gloves), correct order of cleaning for both daily and terminal cleaning, time allowance for cleaning agents to properly work, and teamwork.

Video two “Cleaning Nursing Home Contact Isolation Rooms”: the identification of high touch surfaces within a nursing home contact isolation patient/resident room setting, correct order of cleaning for both daily and terminal cleaning, hand hygiene strategies, protocol in entering and leaving rooms.

Video three “Hand Hygiene and Infection Prevention in Nursing Homes”: correct implementation, order, procedure and disposal of diaper change, foley catheter change and wound/dressing change.

Once strategic initiatives were identified and learned by the artistic producer/research choreographer, a creative team was assembled which included dancers who would be the instruments to convey the necessary information, a film videographer to film and assist the producer/research choreographer in editing footage into a cohesive story video, a musician to create original music to circumvent copy-write issues, and a lighting designer to craft evocative lighting to enhance and add atmospheric nuances to sequences which would be filmed indoors on a proscenium stage.

The creative research process commenced with the generation of a storyboard that would thread the schematic material and propel the video through sequences in a logical pattern that best served both the directives needed for information and the choreographic process. When this key skeletal ingredient was finalized, the dancers were brought into the process to begin the development of experimentation with movement motifs and props when applicable to begin the procedure of choreographic progression that fashions a dance language using the human body as the instrument and embodied movement to communicate ideas to an audience.

Gathered in a dance studio after hours, the progression of these research projects relied on trial and error of taking a task such as the assembly of items necessary for a cleaning cart, and creating a dance sequence that not only incorporated the actual items of cleaning agents, brooms, wipe cloths and spray bottles, but was also choreographed with the idea of illustrating teamwork in mind. Other dance sequences for the medical videos revolved around the conceptual particulars of donning and doffing of protective clothing including gowns and gloves, gestural images of strong manual cleaning, exhibiting medical support equipment including diapers, foley-catheters and items necessary for wound/dressing changes and transitional dance arrangements to bridge the segments together.

Once these directives were established in a dance language, sequences were filmed serially as best as possible aligned with the previously established storyboard. Creatively, this included multiple shots to achieve the highest level of technical proficiency paired with logistical spacing issues and lighting adjustments to achieve the desired look of any given segment. These filmed pieces were then scrutinized by both the producer/research choreographer and videographer alike to choose which of the many shots filmed best represented the integrity of the intended characterizations.

The selected sections were then spliced together for a rough draft depicting the storyboard brought to life. To complete the dance/music video model, original composed music fashioned with a pop-culture dance club motif was invented. The determined choice to utilize dance club music was planned as it projects energy and vitality, and was thought to be a musical style that would capture and keep attention. The rationalization to use this type of music also included the thought that if the video was perceived as entertaining, then it might potentially encourage multiple viewings, thus directives included educationally might have a better chance to be recognized or remembered. This musical choice was also paired with a classical remix to add variety to the video.

The freshly minted music sections were then inserted to the framework of the video footage to complete the initial creative phase of the project. The video was sent to The Florida Department of Health as a preliminary version for their inspection of procedural correctness. Further editing and re-shooting of certain sequences became necessary to tweak and rectify details which inadvertently depicted incorrect aspects of certain medical necessities.

When a final version was approved by all parties involved, the video was released to The Florida Department of Health, and entitled “Cleaning Patient High Touch Surfaces.” It received positive and enthusiastic response for its innovative means to communicate the necessary information to the respective staffs who viewed it. A testament to the appeal of this method of education was further demonstrated as the video was requested and used by hospitals across the United States, and even internationally in Poland and Canada.

Feedback

The critical response from The Florida Department of Health stated: The video developed by The University of South Florida School of Dance met the intended objectives as well as communicated the concepts of teamwork, cleaning agents may require contact time (ie: time for cleaning agent to remain on a surface before it is wiped or cleaned) and the need to scrub some surfaces as opposed to gently wiping. In addition, the video demonstrated the proper way to put on and take off gowns and gloves as well as the importance of removing gowns and gloves and properly discard them prior to exiting the patient room. Hand hygiene was also emphasized as well as the high touch surfaces that need to be cleaned to help prevent the spread of infections.

The video was distributed to collaborative participants to assist them in meeting their educational needs for ensuring the cleaning of high-touch surfaces. In addition, we have found that our tools for the collaborative have been helpful to many other healthcare facilities, including long-term care facilities, and anticipate this will hold true for this innovative training video. The long-term care community was very receptive to this form of training and requested a similar video be developed specific to a nursing home. Though an innovative approach to training, videos such as these have been motivating while also providing important information to help promote behavior change. (Burke)9

To further gauge the effectiveness of this model, a questionnaire was sent to the hospitals which incorporated the video into their individual training programs. Of the responses received, it was unanimously agreed that the video appeared to engage the staff, that the messages using dance as a language were sufficiently informative, the video contained useful information and that dance can be used as a training tool to communicate information.

The success of the video led to two later commissions from The Florida Department of Health. “Cleaning Nursing Home Contact Isolation Rooms,” and “Hand Hygiene and Infection Prevention in Nursing Homes” were developed for the Nursing Home environment, which presented different strategies in that the setting differed from the more transient atmosphere of a hospital to one of more permanence. This necessitated the learning of distinctive schemes relevant to this type of particular location.

Once the directives specific to the Nursing Home setting were identified and learned, the research process for the ensuing two videos echoed that which was established for “Cleaning Patient High Touch Surfaces.” Each incorporated dance sequences that were once again developed to string communication via movement in accordance with a storyboard that had been envisioned. Pop culture club music was again chosen and paired with classical remixes to accompany both videos to infuse energy and vibrancy into the finalized products. Similar to the initial video, the response has been complimentary and affirmative for their respective contributions to the educational aspects they present in an original fashion.

Social Issues

The success of the medical videos attested to the appeal and effectiveness of this innovative format to create awareness and engage interest. Due to this success, the continuation of this creative research agenda progressed with envisioning this venue as the platform to serve as a vehicle to illustrate social issues. This idea was particularly geared towards the teenage demographic, who seek out dance music videos for entertainment purposes, and who also could benefit from repetitive viewings of this popular medium if laced with informative information. When one considers the vast lot of social issues beckoning for attention, many come to mind, bullying among them. Bullying was chosen from among several social problems to depict, due to its relevancy as one in escalating prominence. Part 2 will chronicle the development and success of the Bullying video, the video which followed geared towards domestic/dating violence, and the projected new video on suicide awareness.

References:

1. Nora Ambrosio, “Learning About Dance, Dubuque, Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company 1999.

2. Inge Baxmann, “RESOURCES AND RICHES AT THE BOUNDARIES OF THE ARCHIVE: MOVEMENT, RHYTHM, AND MUSCLE MEMORY A REPORT ON THE TANZARCHIV LEIPZIG,” Dance Chronicle 32 (2009): 127-135

3. Dr. Sunday Doutimiariye Abraye, Rudolph Kansese, “DANCE AS A MEANS OF COMMUNICATION: THE OWIGIRI DANCE EXPERIENCE,” The Dawn Journal Vol. 2, No. 1 (January – June 2013)

4. Inge Baxmann, “RESOURCES AND RICHES AT THE BOUNDARIES OF THE ARCHIVE: MOVEMENT, RHYTHM, AND MUSCLE MEMORY A REPORT ON THE TANZARCHIV LEIPZIG,” Dance Chronicle 32 (2009): 127-135

5. “Definition,” Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER) Accessed June 10, 2013. Last modified November 3, 2010, http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/c-difficile/DS00736

6. Robin B. McFee, “Clostridium difficile: Emerging Public Health Threat and Other Nosocomial or Hospital Acquired Infections,” Disease-a-Month Volume 55, Issue 7 (2009) 439-470

7. Lucy Irving, “The British Psychological Society” Accessed November 22, 2013. http://www.bps.org.uk/news/bps-funded-dance-films-explaining-statistical-concepts-launched-online-0

8, 9. Anne Carol Burke, Healthcare-associated Infection Prevention Program Manager

Florida Department of Health, Bureau of Epidemiology, interview 2012

(Andrew Carroll is Assistant Professor, Dance, School of Theatre and Dance, The University of South Florida, College of The Arts.)