Art Review: The “Hairy Who?”

1960s Politics at the Art Institute of Chicago

By Gail Levin© 2018

arttimesjournal November 14, 2018

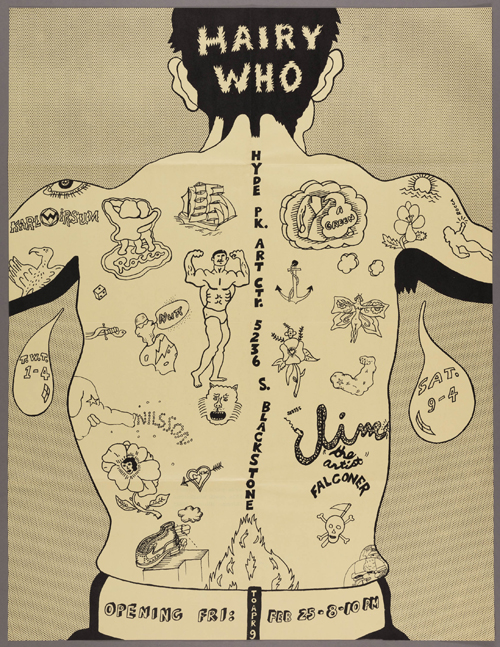

Jim Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca, and Karl Wirsum. Hairy Who, 1966. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Gladys Nilsson and Jim Nutt |

“Hairy Who?,” shown at the Art Institute of Chicago (September 26, 2018 through January 6, 2019), offers a fine–tuned historical survey of a key chapter in the visual sensibility of Chicago. The moniker, “Hairy Who?,” was chosen casually by six young artists to promote their mostly figurative art in six shows (1966-1969): first three shows at Chicago's Hyde Park Art Center, then one at the San Francisco Art Institute(spring 1968), one at New York's School of Visual Arts (1969), and a third later that year at the Corcoran Gallery of Art (Washington, D. C).

Though I only arrived in New York after 1969, I did get to see some of these artists among the “Chicago Imagists,” often on view during the 1970s at the Phyllis Kind Gallery in Soho. "Chicago Imagists" confused the Hairy Who? six—Jim Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca, and Karl Wirsum—with other imagists from Chicago, such as Roger Brown or Ed Paschke. The present show, however, sets the record straight, outlining how these six came together through the Art Institute of Chicago, where they all attended its school as young adults, although Nilsson and Wirsum had started even earlier at its Junior School, and Rocca attended members' courses, which taught drawing from a live model posed on the auditorium stage.

The current exhibition documents how the group, fresh from art school, set themselves the goal of winning attention even beyond the confines of Chicago. Each of the six original shows and the six artists gets full attention in the hefty book-length illustrated catalogue, replete with posters, catalogues, checklists, and price lists. Looking at the modest 1960s prices could make one regret missing out. They asked from $35 for a pen and ink drawing by Jim Nutt to $650 for some of the group's larger oil paintings. Fabulous watercolors by Gladys Nilsson went for as little as $125!

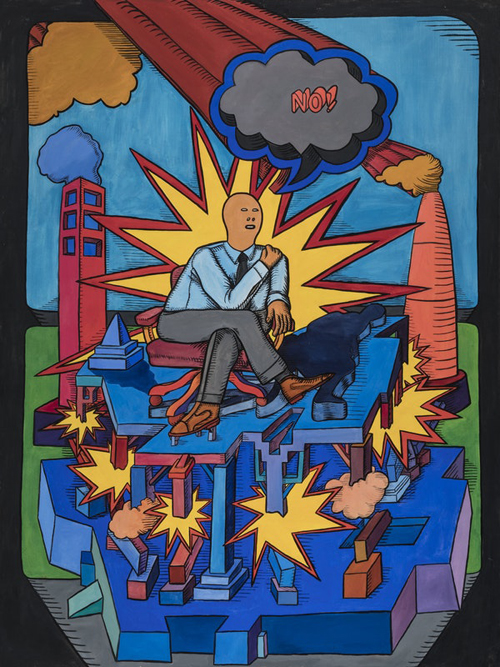

Art Green. Consider the Options, Examine the Facts, Apply the Logic (originally titled The Undeniable Logician) , 1965. Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, Anonymous Gift. © Art Green. |

It's worth noting that two of the six in the “Hairy Who?” were women, an unusual number for that time. Without headlining politics, the work of all six reflects and addresses the hot issues of the sixties. Chicago, it must be said, was a nexus for a number of significant events: from the opening of the first of Hugh Hefner's infamous Playboy Clubs, featuring young women waitresses, scantily clad as “bunnies,” which opened in Chicago in 1960, to the uproar at the infamous Democratic National Convention in August 1968 in the midst of the controversy over the Vietnam War.

The art reflects on the war: Art Green's Fat City Phenomena (1968) features a red and blue cannon aimed at what looks like a Dairy Queen ice cream on scaffolding, suggesting that war could destroy a good situation. Even more obviously, Green's huge anti-war canvas of 1965, called Consider the Options, Examine the Facts, Ally the Logic ( originally titled The Undeniable Logician), depicts a seated figure based on a 1963 profile in Time magazine of Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, one of the chief architects of the U.S. escalation of the war. He is shown faceless before billowing smoke and explosions in the center of a canvas that features just one giant word in a thought balloon: “NO!”.

A more humorous take on the military debacle is Gladys Nilsson's Duck Patrol (originally titled Duck Troops) of 1966. Her watercolor rendition of troops as ducks is complete with red, white, and blue banners, military stars, a bugle, and a flag with a five-pointed central star resembling that of the Vietcong, shown waving from the bill of one of the “ducks.” One suspects that she was making a subtle reference to slang meanings for ducks: gullible or easily fooled people; facile targets for trickery; those who are easy to con, since a real sportsman doesn't shoot a “sitting duck.” An easy victory was then part of U.S. government propaganda at the same time U.S. was escalating troop levels before the disasters of 1968, such as the Vietcong's Tet Offensive and the Mylai massacre by American troops.

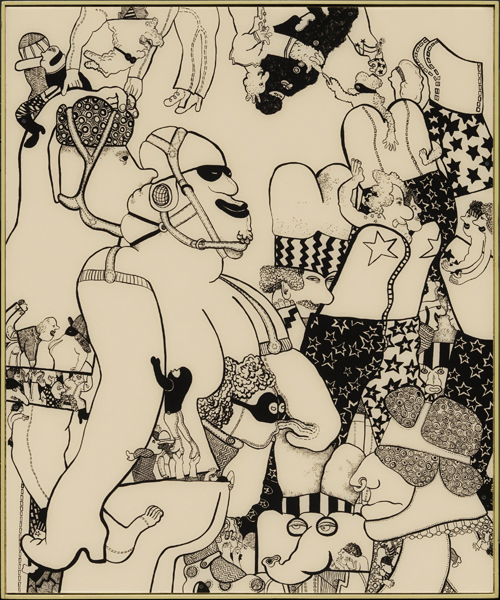

Gladys Nilsson. The Trogens, 1967. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago. © Gladys Nilsson. |

In The Portable Hairy Who!, the comic book that the group produced as a catalogue for their 1966 show, Jim Falconer's black and white drawing inside the back cover reads across the top: “SMASH RRRUMBLE1 KABOOM FLASH; Dig this offer; KA-POW; YOUR OWN SURPLUS WAR,” but in the bottom corners asks, “Are you YELLOW? And commands, DON'T BE CHICKEN.” His imagery includes the head of a G.I., a jeep, a bugle, a parachute, a handgun, a rifle, and struggling figures to convey the idea of battle.

More anti-war imagery appears in works by Karl Wirsum shown in 1967 and 1968: untitled sculptures of a skull and crossed bones that were originally called Skullpture X (1967) and Skullpture #4 (1968). They broadcast youths' widespread fear of dying to make Vietnam “safe for democracy.”

Also contested during the 1960s, eroticism and feminism—or at least jokes about them—are on view. Jim Nutt's 1966 Miss Stake puns and parodies a beauty-queen contestant, though it was two years before the visible feminist protests disrupted the Miss America pageant in 1968. Organized by a group identified as “New York Radical Women,” the protests, held on the Atlantic City boardwalk, captured attention by discarding symbolic feminine products, including bras, hairspray, makeup, girdles, mops, and other items into a "Freedom Trash Can."

The female figure Jim Nutt showed in 1968, captioned Wet Pants Hot Breath, suggests that he was at least aware of sentiments that would cause the protests in Atlantic City, just a few months later. His drawing is captioned across the top, “I can't stand it.” By the time of the SVA show in February 1969, Art Green produced a drawing called Passive Sanitation, depicting a female head asleep, her nose wrapped, ignoring three parked vacuum cleaners below. The same female head appears again next to a corseted female torso in a 1969 drawing called Anita's Night.

Karl Wirsum's 1969 series of monstrous “Show Girls” suggests that he too was thinking hard about gender stereotypes. That same year, he produced a poster-like image of a female face in the shape of a heart for Valentine's Day, captioned “Your Ideal Love Mate,” and subtitled “MADE FOR THE WESTERN MARKET.” Her face is superimposed against a background of red insect-like creatures.

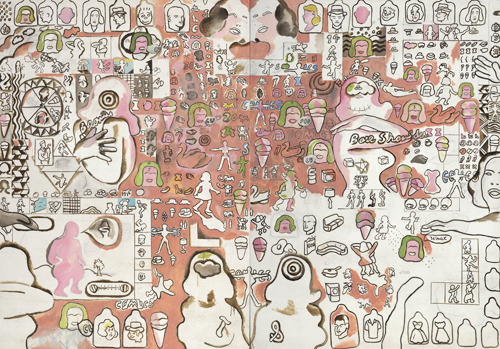

Suellen Rocca. Bare Shouldered Beauty and the Pink Creature, 1965. |

In contrast to Wirsum's monstrous girls, Suellen Rocca projected a child-like innocence in works like Bare Shouldered Beauty and the Pink Creature of 1965, which recalls both game boards and miniature dollhouse furniture. Rocca, who included toward the top center of her crowded composition the word, “COMICS, juxtaposed female torsos with images of ice cream cones and children playing. In the Hairy Who?'s comic book catalogue of 1966, she depicted a “Poodle Woman,” melting ice cream, and tropical landscape vistas, clearly not from Chicago.

If Rocca projects innocence, Nilsson suggests a more heroic image of woman. Her Mt. Vondervoman During Turest Rush, a 1967 watercolor, depicts a kind of female Mt. Rushmore portrait bust with tiny figures of tourists climbing all over the monumental image. Despite working in the delicate medium of watercolor, Nilsson's women exude strength. In her Pollutionville: Home of Bad Air of 1968, she depicts a clothed female with an elephant's head; her breasts are topped off by stars to mark her heroic nipples. Nilsson's concern with environmental peril prompted her to stop painting in oil and turn to watercolor when she was pregnant with her son, Claude, born in 1962, the product of her marriage (now of 58 years' duration) to Jim Nutt.

The figuration of Nutt, Nilsson, Rocca, and Wirsum is particularly idiosyncratic. To some, myself included, it seems to be created in a Chicago tradition that goes back at least to the magic realism of Ivan Albright (1897-1983) and continues through the expressive figuration during the 1950s of Leon Golub (1922-2004). I have long been fascinated that Gladys Nilsson and Judy Chicago (né Cohen) graduated in the same Chicago high school class and studied with the same art teachers, while both also attended classes at the AIC Junior School. Can it be that this quirky figurative style was like mother's milk that the artists drank at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where they all did time?

Jim Nutt. Miss E. Knows, 1967. The Art Institute of Chicago, Twentieth-Century Purchase Fund. © Jim Nutt |

Antonia Pocock writes in an essay in this AIC catalogue that the “Hairy Who?” “personalized Pop,” and suggests that these artists drew influence from Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg. There is the obvious mutual interest in comics and in the case of Oldenburg, the emphasis on dramatically shifting scale, which is very important to members of the “Hairy Who?,” especially Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, and Art Green. What Pocock missed, however, was that Oldenburg, the son of the local Swedish Consulate, grew up in Chicago, which is also a likely reason for what the “Hairy Who?” and he have in common.

After his graduation from Yale in 1950, Oldenburg, too, attended classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, before settling in New York. Oldenburg remarked: “There's the sepulchral feeling I get about Chicago, perhaps because it's so perpendicular—like tombstones.”* Yet we can find probable visual cues for Oldenburg's enlargement of scale and his soft sculptures in Salvador Dali's paintings, some of which were discoverable right in the galleries at the Art Institute.

The school's buildings were then physically connected to the museum. The collection left its mark on both faculty and students, including the “Hairy Who?”. Dada and Surrealism had an early and serious presence in the AIC's permanent collection, where Duchamp's intimate, Mary Reynolds, donated her own collection in 1951. By then gifts from others included major paintings by Dali: in 1943, his Inventions of the Monsters of 1937; and in 1949, Mae West Face which May be Used as a Surrealist Apartment (1934-35).

Who knows if either Oldenburg or any of the “Hairy Who?” ever caught a glimpse of an old advertisement for Chicago's own pack of Wrigley's chewing gum-- magnified well beyond normal scale. Chicago remains a city of outsized heroic skyscrapers and artists whose originality rests in their eccentric refusal to conform to traditional standards and styles developed elsewhere. The “Hairy Who?” exemplify that individuality and stubborn idiosyncracy.

This exhibition was co-organized by Mark Pascale, Janet and Craig Duchossois Curator of Prints and Drawings, and Thea Liberty Nichols, Researcher in Prints and Drawings, with Ann Goldstein, Deputy Director and Chair and Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Art Institute of Chicago.

* Claes Oldenburg interviewed by Paul Carroll in Claes Oldenburg: Proposals for Monuments and Buildings, 1965-69 (Chicago: Big Table Publishing Co., 1969), 29.