Al Jolson and the Birth of the Rotten Musical

|

By FRANK BEHRENS

ART TIMES January/ February 2010

HOW MANY EARLY musicals can one watch without wondering (1) why are so many based on the characters putting on a show and (2) why are the plots so alike? One might answer the first more easily: the musical-within-the-film provides ample excuse for the songs. The second question is not all the simple.

The very earliest of musicals, those that were made directly after “The Jazz Singer” in the late 1920s, so exploited the novelty of sound that little attention was given to believable characterization and dialogue or to really interesting plots. If the public did not demand them, why bother to offer them?

Well, recently six ancient films starring Al Jolson have been issued as part of a Warner Bros. series of DVDs called the Archive Collection. Many films that have never appeared on disc will make up the series.

The rotten plots, deplorable acting, and terrible dialogue were apparently all forgiven by audiences back then, because purpose of the films was to give Jolson as many chances as possible to sing, with just enough dialogue to justify the whole thing being a movie. For those who can’t stand Jolson—and I am one of them—watching them will be a chore. But as I am a student of the Hollywood musical, watching them was also an education. All that was bad in the early musicals—not to mention most of the later ones—can trace its way back to the films just like these.

“The Singing Fool” (1928) includes several silent segments, as did the milestone “The Jazz Singer.” Jolson is a singing waiter named Al Stone who succeeds and loses all. Top songs are “Sittin’ on top of the world” and “Sonny Boy.”

“Say It With Songs” (1929) has Jolson in prison for murder (!), still singing too much of the time, with no song at all to recommend the whole.

“Big Boy” (1930) is a film version of a Jolson stage play. Here he plays entirely in blackface (until the very end), while the plot is concerned with a horse and the Kentucky Derby. The songs are forgettable.

“Wonder Bar” (1934) has him named Al Wonder, owner of the Wonder Bar. Some early choreography by Busby Berkeley is interesting, as well as the cliché of a small stage expanding to the size of an airplane hangar for the production numbers. There is also an early example of a camera shot from directly above as the dancers form kaleidoscopic patterns. At least Dolores del Rio looks great, while Ricardo Cortez plays the nasty and Dick Powell warbles. (How much better Powell was to be playing the hard boiled detective in “Murder My Sweet” ten years later!)

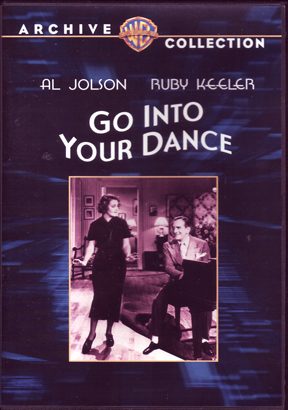

“Go into Your Dance” (1935) is Jolson’s only pairing on film with wife Ruby Keeler, who seems to display little talent in singing, dancing, or acting. It is, of course, a musical about putting on a musical. Again, the stars were the draw, not the material.

“The Singing Kid” (1936) is just that. It starts with a medley of songs from the earlier films and gives us Cab Calloway as some welcome relief from Jolson. Even the team of Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg could not come up with any hits. The mushy sentimentality of the plot sinks this one from the start.

Among the other negatives are Jolson’s rotten acting (although he does have his moments when he is not trying to act), his smug egotism that so clearly shows a lifelong love affair with himself, and the use of blackface that so many found offensive even back then and more do today.

Among the positives, as I mentioned earlier, is the historical interest of these films. Not only are they a moving history (in both senses of the adjective) of social attitudes back in the Depression years (the ones of last century, not this one), but it is fascinating to watch the clichés develop that will be copied over and over by so many other Hollywood musicals.

fbehrens@ne.rr.com