Two for Tango, Tango for Millions

By Dawn Lille

ART TIMES May/ June 2010

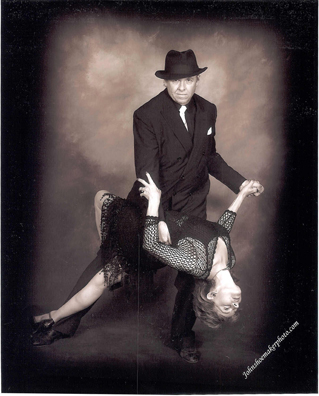

Amy Laraignee and Ray Hogan Amy Laraignee and Ray Hogan |

The sensual, focused and complex dance called tango, long associated with Argentina, was the rage of the American social dance scene in the early 20th century, gathered more and different fans as a form of entertainment with the 1985 Broadway production Tango Argentina, and now has millions of ardent followers all over the world who think nothing of pursuing it several nights a week or travelling half way across the world to study it.

Tango as we know it today developed in the late 19th century in the area around the Rio de Plata in South America, specifically Argentina and Uruguay. The term “tango” derives from the Bantu language of Africa and can mean “drums” or “a social gathering with drums.” At the end of the 18th century African Argentines comprised a large segment of the population of their country. Both they and European Argentines danced condombe, tambo and tango, all soon prohibited, due to the influence of the missionaries, who considered them indecent.

By the end of the 19th century European immigrants, mostly Spanish and Italian, became the majority who brought with them such dances as the waltz, polka and mazurka, which were then absorbed into the dances of African origin.

Danced in the suburbs as well as urban areas such as Buenos Aires and Montevideo, tango was originally seen in brothels as danced by young, poor male immigrants. But it was also enjoyed outside on the patios of the crowded conventillos or tenements, where the Spanish, Italian and Polish newcomers lived. Like so many things originally considered immoral or improper, it attracted the sons of upper class Portenos (inhabitants of Buenos Aires), who frequented the brothels and also danced at the outdoor parties.

In 1907 it went to Paris and by 1915 it was the craze of Europe and eventually the United States. In both places it became more proper and stylized, leaving out the suggestive body movements, pauses and complicated leg variations of the original dance. When it returned to the dance halls of middle class Buenos Aires it still had the elegance and studied walk, rhythm and tempo of its ancestor, but it was much smoother. Contemporary Argentine tango has brought back some of those early movements.

Recently my partner and I went with friends to Argentina and Uruguay. We had envisioned experiencing a bit of tango ’midst our touring, but were not prepared for our immersion in this infectious cauldron of physical prowess, technique, determination – and fun.

Omar Quirogo teaching the Zamba Omar Quirogo teaching the Zamba |

We stayed at Conventillo de Lujo. Owned by Amy Laraignee and Ray Hogan, it has been in existence for five years. To some extent it was influenced by the idea of the original conventillos, which were actually a series of airless single room dwellings, mostly for men, who danced in the open-air patio to escape these rooms. Amy and Ray bought two buildings, converted them into apartments and connected them via a glass roofed patio. Their aim was to create a place, a community, a home for tango.

Amy, born in Argentina, danced tango before an automobile accident that left her unable to walk, and, with fierce determination, later returned to dance, winning wide acclaim. She lived, competed and taught in Michigan for many years. Ray was born in Alabama, raised in Indiana, graduated from Purdue and went to work for Ford. They met in a class at Arthur Murray’s in Dearborn in the mid-80’s and were active in ballroom dance. They joined to form the Latin and Argentine Dance Club of Detroit in 1993.

The first thing seen upon entering the Conventillo is the life size statue of two tango dancers. As one goes up the stairs past the sienna colored walls to the different apartments, there are dozens of photos of tango dancers, Amy and Ray included, as well as posters, more statues and green plants.

On the first floor the glass roof, which is on the level of the third story, covers a large area that is part large open kitchen, part dining room with one big table and part sitting and computer room. Adjacent and open to it is the mirrored dance studio, with a smooth wooden floor, round red pillars and an excellent sound system. During a hearty breakfast one can gaze at the yellow, green, gold and blue walls or the assortment of ceramics and greenery, while listening to the tango music, to which a couple may be practicing or a class being taught.

For many in the large Canadian contingent there with us, this was a repeat to study and learn more. They not only dance at home, but some of them teach as well. We also met guests from France, England and Australia. The South Africans came after we left.

The tango is a dance of close embrace in 4/4 time that moves counterclockwise. The man leads firmly and absolutely. His moves create many dance figures or patterns and the woman must intuit his steps, adding her own embellishments and twirls. She must feel the cadences, especially the pauses, which are an integral part of the dance, interpreting the messages her partner sends.

The stylistic basis for all tango movement is the figure eight (ocho), which comes from the African condombe. Not only do the legs often create this shape, but every step passes through the center of the body, knees and ankles briefly touching, much like the center off a figure eight.

There is a basic eight count step that stresses posture, elegance and exactness. The structure is non-rigid and allows for much improvisation, but that is in the order of the steps and the embellishments, not the steps themselves.

Two of the best know musicians associated with tango are Carlos Gardel, the singer and song writer and Astor Piazzolla, the composer who fused tango, jazz and classical styles. Instruments have come to include the violin, guitar, flute, clarinet, mandolin, piano and the bandoneon, a form of accordion.

Our first class was with Xavier, a solid, intense and gentle Argentine, who stressed the element of smooth, elegant walking in learning the tango. The four of us took a private class with him later in the week and in-between took one with Ricardo (a Chilean who lives in Calgary and for whom this is an avocation) and another with Omar, a tall Argentine who looks like a flamenco dancer and was assisted by his very pregnant wife and dance partner, Veronica. We were instructed to breathe, to move only our lower bodies and to glide. Exhausted by the deep concentration required, we persisted even though we were told it takes at least six years to make a really good tango dancer.

The term milonga originally described an improvised song to which movement was added. Today it refers to both a tango-like dance, which preceded the tango and was considered indecent, and to a dance party, usually in a dance hall, dominated by tangos and milongas. The latter is a bit faster, with a six count basic step.

We went to four milongas, three in Buenos Aires and one in Montevideo. Amy and Ray took a group to the first, held in the neighborhood community hall, to celebrate Amy’s birthday. When we arrived someone was teaching a folk dance to the younger members of the crowd. This was followed by a brief class in salsa. The rest of the evening was devoted to tangos and milongas.

What amazed us was that the excellent dancers of all ages were, for the most part, just ordinary people from the neighborhood who were very serious about their dancing. There were some, in their eighties (we asked) who, off the floor looked old and frail, but once their dancing shoes touched the sacred place they were transformed. And what dancing shoes – high heeled t-strap sandals for the women, often elaborately decorated in a myriad of colors, and slick, often two-toned footwear for the men.

The party held the next night at Conventillo was smaller, but still filled the studio. It began with Omar teaching the Zamba, a flowing courtship dance in which the woman uses a long scarf. In some ways it reminded us of a Renaissance court dance, from which it is probably descended. After a few hours of tango we were entertained by a group of seven men called Tres al Toke, La Cuerde Condombe, who played African style drums. One of them was Julio, a taxi driver who lives at Conventillo and is a marvelous dancer.

The outdoor milonga a friend took us to on a Friday night was held in a circular covered space in a large park in the Belgrano district and was free to all. The DJ played many milongas and, at times, we were practically running to catch up with the adept and fast moving dancers.

In Montevideo we participated in a milonga held on the upper floor of a 19th century market with soaring leaded glass ceilings. Here there were two rooms, one that seemed to contain the under 50 crowd and the other the over 50 group. Again, the sartorial splendor (shoes worthy of Vogue ads and outfits from elegant to outré) and gliding confident movements, often subtly and seductively decorated, were a cause for admiration.

The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges once called the tango “a way of walking,” but it can also be both poetic and emotional, and many of those in the dance halls are authentic artists. For them, it is almost a religion.