(845) 246-6944

· info@ArtTimesJournal.com

Artist as Revolutionary:

A Preview of 2006 in Great Britain

By

Ina Cole

ART TIMES Jan/Feb

2006

The idea of the artist as isolated rebel, out of sync

with a philistine society is a popular myth, perpetuated through time

and reaching a peak in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century;

a period that witnessed the development of some of the most radical

ideas in the history of art. The year 2006 presents a number of exhibitions

in Britain focusing on artists who, by means of their chosen intellectual

yet often solitary path, declared war against accepted modes of representation.

Since the Renaissance, painting had used a geometrical system for depicting

the illusion of reality, a concept which became actively challenged

as the artists’ mission became a voyage of discovery and explanation

that profoundly questioned the way in which man viewed the world around

him.

The theme of artist as discoverer is best captured in

Rebels and Martyrs: The Artist in the Nineteenth Century at the

National Gallery, London (28 June-28 August ‘06), which brings together

paintings by many of the nineteenth-century’s most eminent artists:

Caspar David Friedrich, Eugène Delacroix, Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet

and Edgar Degas. The exhibition traces the archetype of the artist from

its origins in Romanticism, to its climax in the works of Van Gogh,

Paul Gauguin, and their Symbolist and Expressionist heirs, including

Edvard Munch, Ferdinand Hodler and Egon Schiele. Western artists at

this time wanted to gain access to the source of creativity itself and

Rebels and Martyrs explores the different personas they developed, from the idealised bohemian

and dandy, to the priest, monk and martyr.

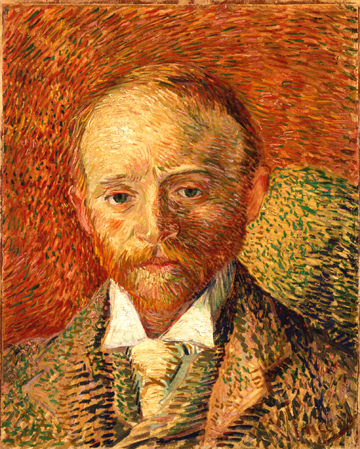

If there is one artist whose tortured existence holds

particular fascination, it has to be Van Gogh, one of the greatest nineteenth-century

Dutch painters, whose work is epitomised by dynamic brushwork and vibrant,

almost hallucinatory colours, often mirroring his own psychological

state. Although selling only one work during his poverty stricken life,

he has achieved a cult-like status as modern art’s tumultuous bohemian.

Van Gogh and Britain: Pioneer Collectors at Compton Verney, Warwickshire

(31 March-18 June ‘06), is the first exhibition on British collectors

of the artist’s work, consisting of acquisitions purchased in the period

before 1939. By focusing on this early enthusiasm for the artist, the

exhibition reveals important new research on British interest in Van

Gogh, whose unswerving dedication to his ideals and vast output in only

ten years, continues to inspire a wealth of material on his life and

work.

Kandinsky at Tate Modern, London (9 June-24 September

‘06), focuses on the work of this great Russian artist, who although

now considered as the pioneer of abstract painting, had often provoked

controversy amongst the patriarchs of the art establishment. As an accomplished

musician, Wassily Kandinsky’s approach to colour was highly theoretical,

believing that on seeing colour he would actually hear music. In his

works a cacophony of elements explode in the picture space in a manner

previously not attempted, and his search for new forms pivoted him to

the extremes of geometric abstraction. The exhibition charts Kandinsky’s

path towards abstraction in the period from 1902 to 1922, a time when

he became associated with Die Brücke and Blaue Reiter, before joining

the Bauhaus in 1922. This was an extraordinarily fertile period and

the exhibition focuses on the consequences of his innovative discoveries

during the turbulent years of the First World War and the Russian Revolution.

The first major exhibition of the work of Modigliani

held in Britain for over forty years, takes place at The Royal Academy,

London (8 July-15 October ‘06). Italian born Amedeo Modigliani lived

a short life of excess, arriving in Paris in 1906, which was then fast

becoming the capital of bohemian culture. Although his life style was

notorious, in his work Modigliani was highly disciplined, restricting

himself almost exclusively to the depiction of the human form. Without

associating himself with any particular group, he developed an immediately

recognisable style of working, characterised by primal, elongated heads

balanced on disproportionately long necks. The legend of Modigliani’s

life has been cultivated through time, which unfortunately ignores the

intense concentration of works produced in his last years. There is

a curious elegance in his uniformly stretched models and the exhibition

Modigliani and his Models, offers an opportunity to re-evaluate

the artist’s critical reputation, exploring his unique position in the

early history of modernism.

One of the most significant events of 2006 is the 100th

anniversary of the death of Paul Cézanne, who is unanimously regarded

as one of the greatest forerunners of modern art. Although actively

involved in the revolutionary creative ferment directed against the

French bourgeoisie and academism, and working in increasing isolation,

he never the less developed a significant reputation in his own life

time. Cézanne achieved a new synthesis of reality and abstraction, which

paved the way for some of the most pioneering developments of the twentieth

century, first fully expressed in Cubism. Cézanne in Britain

at the National Gallery, London (4 October -7 January 2007), traces

the development of his painting from the 1860s to his death in 1906,

focusing on how Cézanne’s work first arrived in Britain and the role

played by the art establishment in securing the artist’s reputation.

What all these artists have in common was their unwavering

belief in a new order; a radical re-organisation of pictorial systems

to not only challenge notions of academic acceptability, but to bring

to the surface deep physiological states. In many cases the pioneering

aspects of the work at the time of its production was only understood

by the enlightened minority, often taking decades for the majority to

appreciate its full significance. This is unfortunate, as the artists’

aim is often universal, expressing an idealised collective rather than

an individual sentiment. In this context it can certainly be argued

that a work of art does not just signify the relationship between man

and the world he inhabits, it can also be the projection of a world

that does not yet exist, which may explain why the individual concerned

often endures such an intense struggle against conformity in order to

transcend tradition in the name of progress.