By

RAYMOND J. STEINER

ART

TIMES Aug, 2004

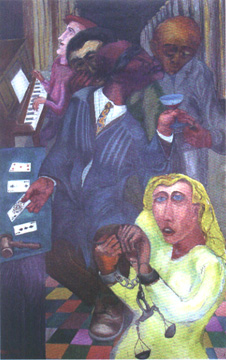

(Photo Courtesy Roshkowska Galleries)

|

|

A POET AS well as a painter, Menahem Lewin uses one of his poems to describe himself as "an outsider always looking in"– and this perhaps serves as a key to his paintings. It is always a danger to interpret a painter's work through biographical details, but Lewin's paintings – large-scale, expressionistic, dramatically negative – certainly let us in on a world where few would wish to tread. A figurative artist whose work is reminiscent of the so-called "social realists" of the 1930s, Lewin draws heavily from Biblical sources in an effort to make visual commentary on a world that few youngsters might recognize today. When not overtly Biblical ("Twenty Pieces of Silver: Joseph and his Brothers;" "Ruth and Boaz;" "St. Sebastian;" "Yehoshua ben Yusef" – the latter, a crucifixion that can only be interpreted as just one more indignity suffered by a Jew), his paintings are of street or everyday scenes that evokes America's Depression era. Street signs ("Newstand"), clothing ("Law and Justice", automobiles ("Journey's End"), are all from an earlier period in American history, all indicative of the unhappy days of poverty, social injustice, betrayal. Not that any of Lewin's imagery is straightforward depiction – neither Old or New Testament subject nor "modern-day" theme is treated in "realistic" manner. Though recognizable as humans, Lewin's figures live in hellish atmospheres (e.g. the overall blood red of "Ruth and Boaz," the surreal townscape of "Journey's End," the moonscape dearth of "Paradise Regained") and most often in dire circumstances. In none do we find any hope of joy, redemption or escape. Titles are most often ironic: the subject of "Journey's End" seems to be a young boy on a donkey, but in the background we see a rifleman aiming at a carload of people milling around and, further in the distance, an airplane on a precipitous dive. Whose journey is ending? In "Paradise Regained" we see a man in uniform, cripples, and heavily-laden émigrés – what kind of Paradise is this? "Law and Justice" seems to be about anything but – we see a blindfolded man playing a game of cards, a manacled woman with a set of scales and a group of onlookers who are unconcernedly drinking alcohol and playing the piano. Even when the subject appears to be light-hearted – "Pierrot and the Flute," "Boy in Nature," "Girl with Balloons" – Lewin's style of ignoring local color and using large, semi-abstract brushstrokes to limn his figures and objects leave us with little doubt that there is something evil in this world, something that, at bottom, distorts and disfigures. The men in "Twenty Pieces of Silver: Joseph and his Brothers" are nearly Neanderthal in their features; the balloons with their dove-like peace signs in the hands of the girl are negated by what seems a stifling atmosphere; the mood in "Boy in Nature," because of its garish coloring that jars the senses, seems anything but bucolic; "Pierrot and Flute" sit in a dismal landscape under a threatening sun (or moon?). In such a world, who would not choose to be an "outsider"? Lewin's power lies is in his consistency of bringing gloom to the viewer – he allows for no ray of hope to penetrate his universe of pain, injustice, false hope, and alienation. One painting, "Everyman's Dream" in which a naked and curvaceous odalisque hovers over a group of men, though ostensibly an answer is, in fact, a twist on the old theme of Lilith – the lure of women's flesh that inevitably brings man to his downfall. Lewin's, then, is an inhospitable world, a world where people are of little account (most of his faces are nondescript, sketchily drawn, sometimes merely blobs of paint that suggest a head and nothing else, a world that in almost all respects is a "fallen" one wherein they are doomed to suffering and death. One wonders if, though obviously a man skilled with his tools, Menahem Lewin might not be termed a modern-day prophet rather than a modern-day painter.

*Menahem Lewin: Paintings (Jul 3 - Aug 2): Roshkowska Galleries, 5338 Main, Windham, NY (518) 734-9669

(Editor's note: The village of Windham, New York, boasts a budding art colony that now includes several fine art galleries. In addition to the Roshkowka Galleries, the venue for this critique, just a few doors down is the Catskill County Council for the Arts' long-established Mountaintop Gallery (518) 734-3104/943-3400 which presently has an impressive exhibition of fine-crafted ceramics, "Journey in Clay," and, just a bit a further, Windham Fine Arts (518) 734-6850, whose show, "An American Sampler," showcases some world-class painters (AWS member Michael P. Rocco a prime example). If you need more of a motivation to take the beautiful trip up through the Catskill Mountains, upcoming shows include: Roshkowska Galleries, "Harriet Tannin: Paintings;" Mountaintop Gallery, "Catskill Interiors;" and Windham Fine Arts, "A View from Afar: New Works by Mari Lyons and Librado Romero." Either way, you won't regret the journey, but call ahead for schedule changes.)