Raymond J. Steiner, Editor • Cornelia Seckel, Publisher

(845) 246-6944 · info@ArtTimesJournal.com

|

|

The Welsh Prints of Stuart Evans

By HENRY HUGHES

ART TIMES April 2008

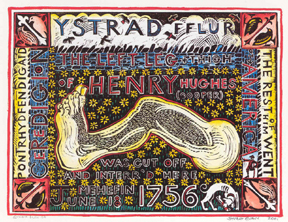

After

walking the seaside city

of Aberystwyth, Wales — my right knee aching from a lorry-dodging

scramble across a narrow street — I sit in a creaky oak chair

at the local Ceredigion Museum studying a man’s leg. Stretched across

a brilliantly colored print, the banded curves of muscle suggest the

anatomical drawings in Grays, but the thick yellowed toes point

to an inscription from life’s less predictable designs: “The Left

Leg & Thigh of Henry Hughes Was Cut Off and Interr’d Here. June

18, 1756.” I glance down to the right, rub my knee

with assurance, and continue: “The Rest Of Him Went To America.”

Roaming over the print’s black lino humor — a backfield of

daisies, the one-legged Welshman cocked for action, a gaunt dog

playing with a bloody bone — I can’t help but smile.

The

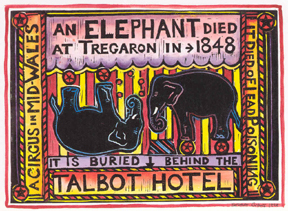

Dead Elephant The

Dead Elephant |

“I like saving things,” Evans tells me after the affable gift shop cashier introduces us. Evans takes a break from his job at the museum — at that moment, cleaning a bust of Edward VII — to talk about printmaking. He is a tall, slender man with energy going into his hands. Gesturing-up a storm, he shows me his print of a wave cresting lifeboat — the three-man craft under bright red sail, bearing down on an arm-flailing castaway. With over sixty miles of craggy coastline, Ceredigion County in mid Wales has an eventful maritime history and many of Evan’s prints depict great ships and busy harbors from the age of sail and steam. Although pirates are mercifully absent from his work, in the print “Smuggling,” one sees a whisky laden launch rowing from a moonlit ship, a glowing lantern in the border design signifying the light of lucre or the law.

Mass production is often seen as the death of original art, but Evans has no pretenses about rarifying his work. “I’m a self-taught print maker and I never worried about limited editions.” He also plays down the craft:

“This is something a kid can do with a chisel and an old piece of floor covering.” The process begins, however, with his ingeniously composed drawings. “My mantra is draw, draw, draw — the ideas come with making and doing.” Evans’ images have just enough realistic prospective and proportion to be taken seriously as human dramas (and he is the master of small gestures like a man pointing to a leaping fish); but there are also cartoon-like elements of narrative and hyperbole that make the images playful illustrations of fortune and folly. To make light of the problem in 1848 of burying a dead circus elephant behind a hotel, he creates complementary images, one of which shows the poor beast on its back, rollers still under its feet, trunk juggling a set of balls. These narratives are enriched with simple, illuminated text and framed by borders of rope, chain or stars that feel iconic not cliché.

Once the drawing is complete, Evans reverses and transfers the images and words onto linoleum and gouges away, checking the progress with a mirror. Occasionally one sees a reversed letter in his finished prints. “It’s a little embarrassing,” he admits. But he sees these reverse typologies as reminders of the process and of the errors inevitable when we attempt to recast the past. Once the linoleum block is complete, Evans rolls on an oil-based black ink and presses the block with paper, rubbing rigorously with a tablespoon. He recalls a time when he used an old laundry mangle for a roller press. “It’s always been low tech and cheap. Now I’ve given up the mangle for a spoon to save space.” Married with three children, Evans works on his art between and after everything else. “There may be a spare hour before bed. We don’t have a TV. I’m tired, but I can still sit at the kitchen table and cut a few lines on lino.” The

Leg of Henry Hughes The

Leg of Henry Hughes |

After

making a single color print, Evans hand paints each image, giving

the scene a carnival brilliance that unifies the story. The blues, reds and yellows seem to sing through the black

background like chords in a salty folksong. Like oral histories and local legends, these hand-colored prints

are also given to variation. “Each print is different. You might

say they are ‘unlimited editions.’ I make a print when I’m asked

for one.” In recent years, Evans has intensified

the colors in his prints, noting that bright colors work well in

mechanical reproductions such as postcards.

Although the brightly colored pageantry of Welsh history

carries many of his popular prints, there is another element of

lino cutting that speaks to a greyer, harder aspect of the land.

Evans has recently been exploring the slate quarries of mid and

north Wales and the way this industry changed the land and people.

“Lino cutting lends itself to the stark contrast of this hard landscape.

You begin to see things that relate to your work practice.”

(Henry

Hughes is a sometime contributor to the pages of ART TIMES)

Smuggling

Smuggling